A common disclaimer found in venture fund subscription documents is:

“Past performance does not guarantee future results.”

Q: But is that really true?—Aren’t established, top tier VCs almost guaranteed to provide top-tier returns?

- There are two types of VCs at issue here:

- Emerging fund managers: VCs on Fund I, II, III <$150 million. Venture capital has generated compelling returns relative to public markets, but only for the top two quartile funds.

- Established VCs are experienced VC fund managers typically with persistent returns. But “persistent” does not mean “superior” returns. Median returns for VC funds in the US have been about the same as public equities (“PME” = ~1.0)—See The persistent effect of initial success: Evidence from venture capital (2020)

- Emerging fund managers: VCs on Fund I, II, III <$150 million. Venture capital has generated compelling returns relative to public markets, but only for the top two quartile funds.

Established VCs vs. Emerging Fund Managers.

- Conventional wisdom says that Established VCs hold superior performance over Emerging Fund Managers:

“Unlike other asset classes, past performance in the venture industry is a very good indicator of future success.”

Conventional Wisdom follows a predictable pattern, like this:

- “Manager selection is the key to capturing attractive [LP] returns.” —Cambridge Associates.

- “Nobody got fired for hiring IBM”

- “Nobody got fired for investing in Sequoia.”

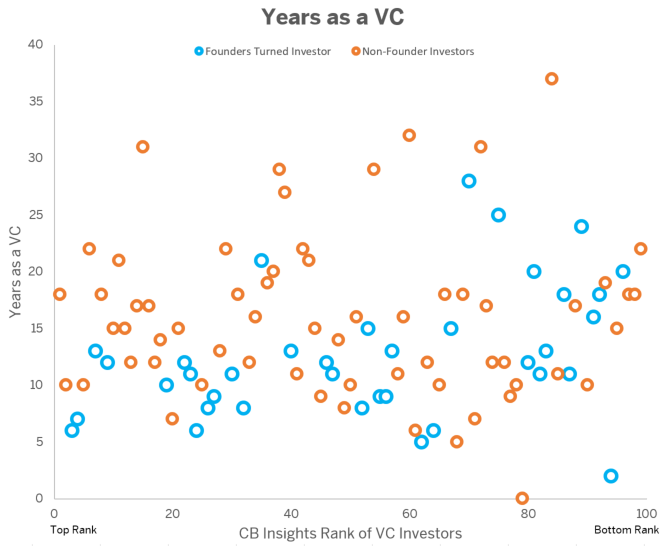

CB Insights Shows Experience Isn’t All That Helpful.

- According to CB Insights, after analyzing the Top 100 VCs in the U.S., this nugget was uncovered:“Interestingly, there was also no relationship between investors’ years of experience as a VC and their rank on the list.”

Persistence of VC Returns

- On August 4, 2020, Michael Mauboussin released an 82-page report entitled, Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look (2020). Here’s a relevant passage: “One important feature of venture capital is the persistence of returns. Exhibit 42 [below] shows that a top quartile fund had nearly a 50% likelihood of being followed by another top quartile fund. Expect a 25% probability of the returns staying in the same quartile if the outcomes were dictated by chance.”

- In other words, if a fund is within the top quartile in Fund I, you can reasonably expect that Fund II will be in the top two quartiles (68% likelihood). However, “[i]dentifying which funds are in the top quartile can be tricky. The reason is that there are different ways to measure results, including various benchmarks, performance measures, and data sources.”

The Case for the Emerging Fund Manager.

- According to Greenspring Associates, an LP with $11 billion assets under management, of the 180 VC funds analyzed under its portfolio management program, emerging fund managers edged out more established GPs (Net Multiple +0.10x; Net IRR +0.87%):

- Alas, the latest report from Cambridge Associates proves that conventional wisdom is wrong! “

- “[T]oday’s market is not the same as 20 years ago. Broad-based value creation across sectors, geographies, and funds means success is no longer limited to a handful of (often inaccessible) fund managers. Moreover, top returns are not confined to a few dozen companies. New and developing fund managers consistently rank as some of the best performers.“

- There are four reasons why emerging fund managers might have slightly better performance than established VCs in today’s environment:

- First, emerging fund managers tend to be made up of a smaller group of GPs or solo capitalists with strong track records. These spin-off funds or managers trade on personal brand which is built over time.

- Second, most emerging firms raise small funds. Smaller funds generally outperform, as a single outlier has the potential to generate strong fund-level performance, even if the fund is only able to garner modest ownership.

- Third, most emerging fund managers do not have to worry about succession plans or experience what happens when there are LP calls to reduce aggregate management fees across funds.

- Finally, the venture capital industry has strong reversion-to-the-mean effects, which implies that the Midas Touch tends to rub off over time—after about 60 portfolio company investments (See The Persistent Effect of Initial Success: Evidence from Venture Capital, § 3.2) (“Little, if any, persistence [occurs] beyond the 60th portfolio company, implying long-term convergence to a common mean”).

- Three interesting quotes from the journal article referenced above:[E]xperience, on average, has an estimated coefficient close to zero.Interestingly, … the VC firms with the highest initial performance declined the most over time while those with the lowest initial performance improved the most.VC firms with larger numbers of investments converge to the industry average success rate.

The truth lies somewhere in the middle.

- As we reference the following topics: funds, venture fund managers,venture industry and top lists, an open question is whether these advantages accrue at the level of the VC firm or the individual. All evidence points to the individual, but it should be noted that failure rates from Fund I to Fund II may be as high as 85%—which means perhaps only 15% of Fund I funds make it to Fund II. (See Samir Kaji, Slide #11 out of 27). It’s obvious, but VC fund managers who perform well early have a far better chance of surviving later fund cycles than those who don’t.For example, each startup that a VC manager takes public in their first 10 investments predicts an 8% higher IPO rate on any subsequent investment. Similar with M&A exits: One sale in the first batch of 10 investments by a VC results in a +1.8% chance higher exit rate (or a +3.6% difference relative to the average). It’s not just that initial success improves access to deal flow, it predicts the probability of future success after ~50 subsequent investments. Success may breed success, but in venture capital, that wears off over time (See Persistent Effect of Initial Success: “[S]uccess rates appear to decline with experience”). Ultimately, VC firms with larger numbers of investments converge to the industry average success rate.

Conclusion.

The bottom line is that emerging fund managers have a slight edge compared to established VCs in terms of fund performance.

Other Articles: